EDITOR’S NOTE: This article originally appeared on The Trillium, a Village Media website devoted exclusively to covering provincial politics at Queen’s Park.

After PC Leader Doug Ford railed earlier this month against social assistance recipients “sitting on the couch watching the Flintstones,” several employment services workers say his system overhaul has made it harder to get those people working — and several have had to end their programs altogether.

In 2019, the Ford government embarked on the lengthy process of combining several of the province’s employment assistance programs, including separate streams for those on ODSP and Ontario Works, into one system.

Before, service providers — the organizations, often charities, on the front lines, helping people with disabilities find jobs — worked out provincial funding contracts each year with the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services.

The Ford government’s transformation added a layer of bureaucracy between the service providers and the province: service system managers, or SSMs, were brought in to manage the service providers. These SSMs could be local municipalities, colleges, non-profits or for-profit companies.

The transformation is almost complete as the final two regions, Toronto and the North, will get their SSMs this spring.

The goal, according to several documents prepared by a for-profit SSM, all marked “confidential” but obtained by The Trillium, was to create a more "unified" system and “increase accountability” while cutting admin work and decreasing clients’ reliance on social assistance.

The result, according to several service provider employees who spoke with The Trillium, has been a disaster.

Workers say they now have to deal with mountains of paperwork and massive funding cuts — up to 50 or even 67 per cent in some cases — leaving much less time and money to help the most disadvantaged find work.

Providers end at least 11 programs

The previous system was totally performance-based, providers say, since ministry funding was tied to how many people the service provider could get working.

The new model, however, pays out for each new client taken on by the provider, and only gives “performance-based funding” for each client who works 20 hours per week or more.

Instead of focusing on outcomes, providers say they now have to sign up far more clients than they can reasonably expect to handle to make ends meet — and they’re implicitly pressured to serve those with the fewest needs, since they’re the ones most likely to work 20 hours a week.

Several programs haven’t been able to keep up with the new demands.

Since last year, at least six organizations have ended disability-focused employment assistance programs, or announced that they plan to in the coming months: Abilities to Work, Community Living Upper Ottawa Valley, Community Living Grimsby, Community Living Oshawa and Clarington, Community Living Brant, and the District School Board of Niagara.

Provincial changes have resulted in a 67 per cent funding cut, Community Living Oshawa and Clarington executive director Terri Gray wrote in a letter to clients, employees and employers in January, explaining why the program that had existed since the 1980s will end on Feb. 28.

The new model “has made it impossible for us to continue operating our Program,” Gray wrote, adding that it “fails to adequately address the unique employment barriers faced by people with developmental disabilities.”

The transformation hasn’t just affected specialty service providers — Humber College, Sheridan College, Mohawk College, Collège La Cité and St. Lawrence College have also ended employment programs.

Some said the decision was a result of a broader restructuring in a tough fiscal environment for colleges. Others called out the government.

“After careful consideration and deliberation, Humber has made the difficult decision not to apply for funding under the new model,” said the college’s associate dean, Chantal Joy, citing the “transformation of Ontario’s employment services.”

After 45 years of service, Sheridan’s Oakville-based Community Employment Services shut down last March because of “changes in funding, and service delivery expectations as part of the Employment Services Transformation in Ontario,” the college said.

Internal docs admit to budget cuts

Ideally, the system works like this: someone with a disability walks into their local employment services provider and asks for help finding a job. A worker there asks them some questions about their abilities and interests. That worker then leverages their long-standing relationships with local employers to line up a position that works for both parties.

They’ll help the employer and employee navigate accommodations, provide on-the-job training and coaching, and check in with everyone over several months, or in some cases, years.

It’s a time-consuming but rewarding process. The providers who spoke with The Trillium said they take pride in helping those furthest from the employment system, with the highest needs.

The Trillium agreed to use pseudonyms so they could speak freely without fear of reprisal from their employers or the provincial government, which controls much of their funding.

“We take the really hard people,” said David, who runs a specialist employment services provider in Ontario.

He said his organization spends “weeks and months” getting to know its clients to figure out where they’d fit best.

The previous funding formula included thousands of dollars in funding for up to three years if a client needed additional training or support. The new formula does not include support funding past the first year, according to a June 2024 report from the Ontario Disability Employment Network (ODEN) and Community Living Ontario (CLO).

That cut had a major impact, as employers are no longer confident they can count on his agency to support their new worker, David said.

“It’s a terrible idea to just vanish,” he said.

The SSM for David’s agency is WCG Services, a for-profit company that oversees service providers in the Peel, York and Ottawa regions.

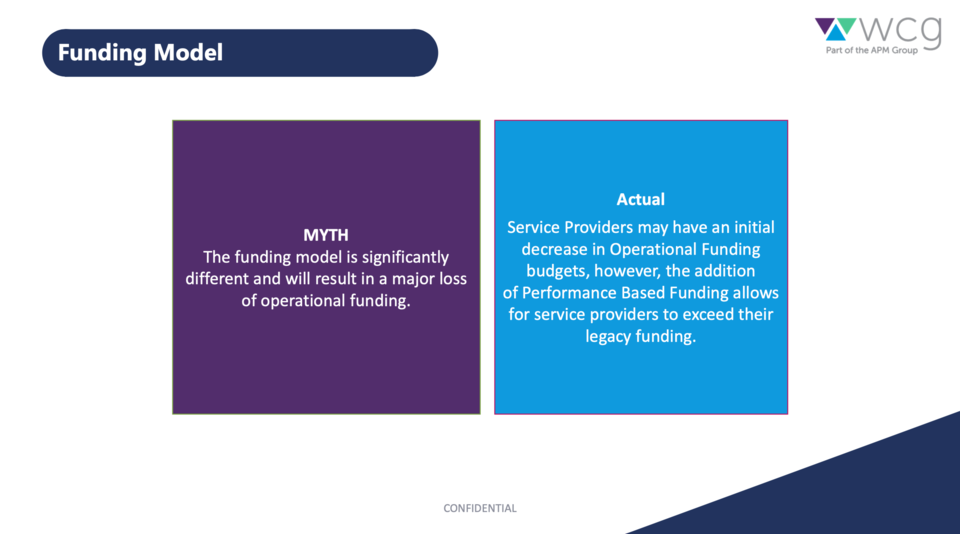

In training slides prepared for its service providers, WCG admits that they “may have an initial decrease in Operational Funding budgets,” but says new performance-based funding means they could make more than they did before.

That performance-based funding is only paid out when clients work an average of 20 hours per week or more.

One “myth” WCG aims to dispel in the slides is that “many ODSP clients only want to or only can work less then [sic] 20 hours.”

A third confidential WCG document obtained by The Trillium refers to clients working under 20 hours per week as “under-employed.”

In reality, the 20-hour requirement is “absolutely unheard of across the world for people with disabilities,” David said.

Many of David’s clients, including veterans with PTSD, have letters from medical professionals recommending no more than 15 hours of work per week, he said.

Since the new system rewards signing up clients (which happens before they get a job), David said his agency has had to take on 300 clients this past year just to survive, instead of its usual 100.

Normally, about 40–50 per cent of clients would end up with a job each year, David said. But in 2024, just 25 per cent of clients on social assistance had completed their “employment action plan,” according to another internal WCG document outlining employment outcomes in one of the company’s regions. That means they are either working, in training, or were referred to another provider, David said.

“We’re just not serving people well,” he said.

"We are proud to work with community partners to deliver integrated employment services in Ontario. Our focus is on creating sustainable employment opportunities for people, and meeting the needs of businesses and communities. IES serves all job-seekers, including persons with disabilities, in progressing towards their individual goals," WCG said in a statement in response to a detailed list of questions. IES stands for Integrated Employment Services, the official term for the Ford government's transformation.

"Working closely and collaboratively with Service Providers is an opportunity to improve the services available to employers and people seeking work, enabling better lives through delivery of IES," the company said.

The PC Party and Ontario’s Ministry of Labour did not comment by press time.

Jane, another service provider employee, said her agency’s strength was supporting clients long-term. That changed when it got its SSM, which The Trillium is not naming to protect Jane’s identity.

That long-term thinking wasn’t “part of their philosophy,” she said.

The year after Jane’s organization switched to its SSM, she said it lost about 40 per cent of its funding for its ODSP-specific employment services program. She said her agency has ended its contract with the SSM and left that program. It now receives funding only from the ministry, at a lower level.

Staff are stretched thinner as the agency works to support everyone with fewer dollars, Jane said.

“We risk deficits now,” she said. “It is very challenging.”

“It just seems that if we had a good relationship and it was working well within the ministry, how do you save money by farming it out?” she said.

Paige and Summer, employees of a Toronto-area employment services provider who often work with people with disabilities, said they’ll be expected to take on about 15–35 per cent more clients when WCG takes over as their agency’s SSM in the spring.

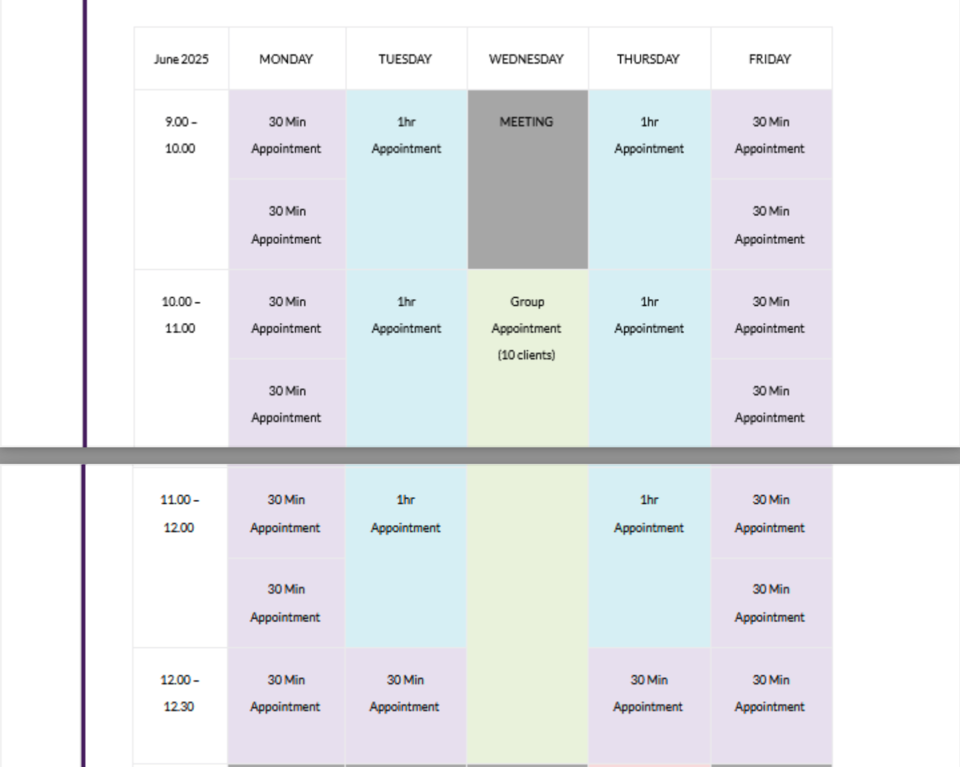

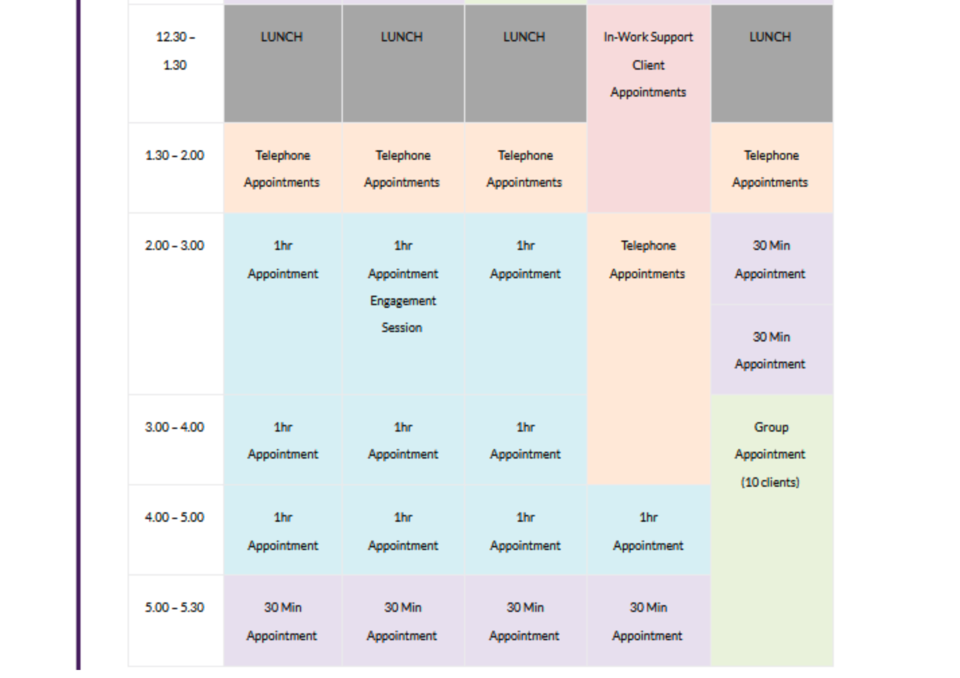

To keep up with the new workload, a mock schedule prepared by WCG suggests employees schedule back-to-back appointments all day, every work day between 9 a.m. and 5:30 p.m., and skip one lunch break.

Summer said much of her job consists of replying to client emails and phone calls. Sometimes clients will drop by the office, she said.

“These things are just not accounted for. It's just not taking into consideration the realities of the role,” she said.

In response to a question during a training session about how to deal with the increased workload, Paige and Summer said WCG suggested that workers take calls on weekends or after work hours.

Their collective agreement forbids that, Summer said. But the fact that it was raised was “scary,” Paige said.

‘A lot of money going into not getting people jobs’

Several providers complained of the increased administrative burden under the new system. The Ontario Disability Employment Network and Community Living Ontario report, which surveyed 68 employment service providers, found that admin work has “ballooned” and staff turnover has been "rampant.”

Under Jane’s former SSM, she said she had to enter information into four separate databases.

Funding is a catch-22, Jane said. To stay afloat, agencies need to sign up more clients, which increases time spent on administrative tasks.

“And you didn’t then have the resources to help the people you had already brought in,” she said.

Since WCG took over, David said his agency has had to hire a full-time employee just to handle the extra paperwork from the increased intake and the case notes WCG requires.

“There’s a lot of money going into not getting people jobs,” he said.

David said the intake questionnaire, known as the Common Assessment (CA), often takes more than 90 minutes for new clients. A copy of the reference guide obtained by The Trillium is 44 pages long.

Previously, Summer said employees would ask clients to describe their barriers to employment, and clients would fill out an information sheet themselves.

A WCG guide to the common assessment, obtained by The Trillium, instructs workers to ask clients whether they have any emotional, psychological or mental health conditions, substance use issues or communication disabilities, and whether they are concerned about their personal safety in their relationships.

Summer and Paige said they worried the questionnaire will harm rapport with their marginalized clients.

“The questions are fairly prying and invasive for that very first meeting. That can really be off-putting to somebody,” Summer said.

‘People want to work,’ despite Ford’s comments

As premier, Ford has suggested that many of those on social assistance, specifically Ontario Works, are leeching off the taxpayer dollar.

He has claimed there are hundreds of thousands of Ontarians "sitting at home, collecting your hard-earned dollars," and has told homeless people to “get off your A-S-S and start working.”

Asked earlier this month about the NDP, Liberal and Green parties’ pledges to double ODSP payments, Ford said "the way you take care of people on ODSP is the economy.”

He denounced "healthy, young people that are sitting on the couch watching the Flintstones," claiming there are “people that have been on Ontario Works, welfare, healthy people, for their whole lives.”

Service provider employees say his comments reveal a deep misunderstanding of the system.

“People want to work,” said Ingrid Muschta, the director of special projects and innovation at the Ontario Disability Employment Network (ODEN).

But workplaces often aren’t inclusive, and a lack of affordable housing, transportation and mental health supports mean people on ODSP or OW often can’t get a job without help.

“This is why specialized services are needed, in order to provide the supports that are needed to overcome the barriers so that people can have access to inclusive workplaces,” she said.

“It’s not a good life on $1,200 when you’re paying rent in Ottawa or Toronto,” David said, adding that some of his clients have to skip meals to make their finances work.

“It's ridiculous to think that someone's just living it up when they're on welfare. That's just not reality,” Summer said. “On ODSP, the amount that people get is so low, they can barely afford to live.”

ODEN’s interim CEO, Amy Widdows, said the Ministry of Labour has been taking feedback from her organization and others about the barriers people with disabilities face under the new employment services system.

A “significant” change is that the province now allows “job stacking,” so people can work multiple jobs to meet the 20 hours per week target, Widows said.

“The ministry is not averse to supporting and coming to events where they can actually learn from the employment service providers and learn what the barriers are and talk about recommendations for change,” she said.

Others are less optimistic.

“Things have not changed since we published Tangled in Red Tape,” said Shawn Pegg of Community Living Ontario.

While some organizations have been finding creative ways to pay for their programs, others “are realizing that they can't go on losing money” and closing up shop, he said.

‘Losing the only neurosurgeon in the hospital’

David said his organization has been burning through its reserves and applying for short-term emergency grants. As the cash dwindles, he said his team is currently discussing whether they can keep the program under the new model.

“If nothing changes, we will have no choice but to withdraw” from the public system, he said, “and continue for as long as we can in a limited capacity with donations and grants.”

Weighing on him is that other providers in his region have told him they wouldn’t be able to take on his high-needs clients if he closes up shop, he said.

He compared the situation to “losing the only neurosurgeon in the hospital.”

There are only a few organizations in Ontario that can help people with disabilities find jobs, Pegg said.

“And so to lose a few would significantly impact the availability of services. But to lose so many at once, I think it's bound to have a really negative impact on people's ability to work,” he said.

Many rural communities have only one such organization, Widdows noted.

“If there's nowhere to go for service,” she said, “then what is someone to do?"