Certain images from the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks are etched in people's minds forever. One of those images is of 'The Falling Man,' taken by Associated Press photographer Richard Drew.

Orillia-based scholar Valerie Hébert uses the photo while teaching the human rights violations and international conflict course at Lakehead University.

"We study images that reflect human rights abuses that document and create memories around conflicts of all kinds," she explained.

Hébert has been a history and interdisciplinary studies teacher at Lakehead's Orillia campus since 2010. She's also an author and editor for Framing the Holocaust: Photographs of a Mass Shooting in Latvia, 1941.

She gets her students to think about what photographs can teach, what they excel at capturing, and what their limitations are as sources of knowledge and understanding.

"I use 'The Falling Man' photograph in the first class of the year," she said. "It's one of those images that helps us to understand just how layered the meanings of photographs are and how deceptive they can be."

'The Falling Man' captures an unidentified male who was trapped on the upper floors of the North Tower of the World Trade Center on 9/11 falling to his death.

"It's this man who has jumped from the tower, understanding that there was no escape with his life," Hébert said. "One of the things that makes it so compelling and unforgettable is its simplicity."

While it was a horrific moment captured by Drew, she says the image itself is calming from an esthetic point of view.

"He's suspended in air, frozen in that moment," she said. "He's perfectly vertical. One leg is bent, but he's in line with the two towers from the angle that the photograph was taken."

The serenity of the image is at odds with what was happening in the photo. In Drew's outtakes, 'The Falling Man' is flailing and visibly falling to his death. It's a more horrific scene.

While the image has become "an iconic symbol" of 9/11, Hébert says it obscures a tragic moment in time.

"It offers kind of a solace," she said. "While it's chronicling a suicide made under duress, it has a soothing effect on the viewer."

While the photo has gained praise over the years, there was an initial outcry from people who felt the image made a spectacle of a painful reality.

"There was total outrage against the publication of that photo because people thought it was one thing too far," Hébert said.

"There were so many other references to suffering in the photographs that flooded TVs and in magazines in the days following, but we have real reservations about those photographs that bring us right up to the moments before and after death."

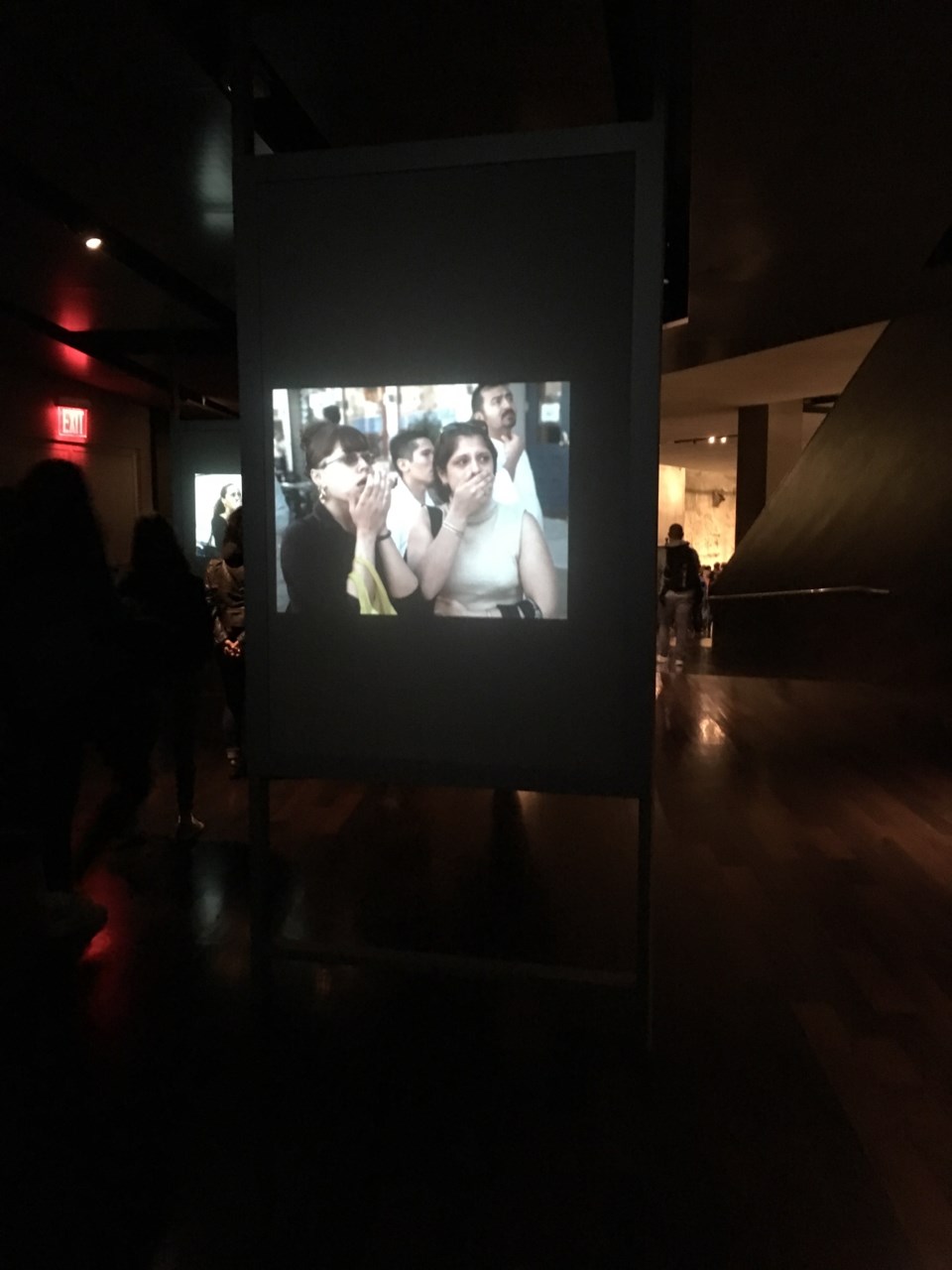

While visiting the 9/11 Memorial & Museum in Manhattan in April 2017, Hébert noticed an exhibit displaying people falling from the towers to their death, but it was seemingly hidden away.

"It's off in a corner," she said. "The museum itself is quite dark, so it would be easy to miss, and there is a wall at an angle, so you can only enter at the side."

Hébert believes the designers of the museum may have been in a state of ambivalence when deciding if the footage should be shown.

"There is a recognition that it might be one step too far in what people can bare," she said. "There are so many artifacts in the museum that are so literal, open and confrontational about displaying the scope and scale of the violence that day, and yet there is that moment where they pull back."

She says there is a general discomfort in photographs that show people suffering because they are relatable.

"When we are trying to connect with the past, when we are trying to understand the lived experience of a past event, it can seem kind of abstract," she said, "but when we see faces, when we can individualize the experience of these complex events, I think that's when we gain a deeper and valuable connection and understanding of the past."

Photographs capturing powerful atrocity often trigger viewers to imagine themselves in the same situation.

"No matter what language we speak, the colour of our skin, or where and when in time we live, we all understand pain, suffering, and the psychological anguish that would accompany a decision like committing suicide in the face of death," Hébert said.

Following 9/11 and the impactful images that came from the tragedy, she believes society has become a more visual culture.

"We now get our news on our phones," she said. "So many social media platforms are photograph based. The image comes first and then we might click on the caption to read more."

While still images can inform how people understand current events, Hébert says it's important to remember a still image is only one person’s interpretation.

"Photographs can be incredibly helpful in understanding an event, but they can also distort how we understand it," she said. "We should always treat images as single piece of testimony."

This story originally appeared in Oakville News' sister site Orillia Today.