In Oakville, the car is undeniably king.

In 2016, about 87 per cent of our trips involved people in cars.

It’s a reality that has clearly led to road congestion and parking problems while contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

But a vision that would see cars become the least prioritized method of transportation across the town seems to have left local councillors both nervous and skeptical.

In 2019, the town hired global consulting firm Steer to prepare an Urban Mobility and Transportation Strategy that would look at town-wide mobility and transportation issues in light of Oakville’s continuing growth.

That $100,000 report was presented at the Feb. 15 planning and development council meeting.

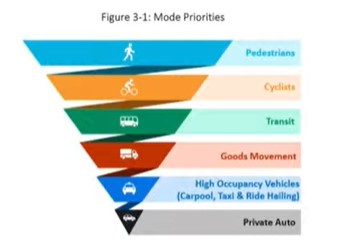

It calls for the town to boot the automobile from its top-of-the-heap position and instead prioritize pedestrians, cyclists, transit riders and vehicles delivering goods.

“People moving in private cars aren’t eliminated from the mix – this isn’t an anti-car type of a strategy – it’s just that their priority as a mode of travel is a lot less moving forward,” explained town senior planner Geoff Abma.

“The focus needs to be on moving people and goods, not cars.”

The move is necessary to allow the town to continue to grow without experiencing gridlock that would force the widening of streets, said Abma.

“We simply can’t make car dependency work while at the same time keeping our town liveable as we grow,” he said. “Cars will always be a part of Oakville, but we really need to focus on providing a whole gamut of other viable and practical choices to move people around other than the automobile.”

Councillors opt not to ‘endorse’ report

Town councillors had been asked to endorse the strategy as a “lens” and “a guiding document” for decision making while giving the nod to a “town-wide communication initiative” to inform people of the strategy and “its importance to the future of Oakville.”

But Ward 3 councillor Janet Haslett-Theall argued the town needed a consultation plan, not just a communication plan.

The strategy offers “a tremendous amount of insight,” she said, but the town needs to understand what would make people buy into the vision.

“We can help people see the future, but we also need to hear from them about how we tackle the tough decisions and how this allocation of scarce resources will affect them,” she said.

Council eventually voted unanimously for an amended motion from Haslett-Theall directing town staff to consult with the public on the strategy and report back to council.

The final strategy is "expected to be presented to council by the end of 2022," according to town staff. Given October's scheduled municipal election, it means the next group of elected officials will likely deal with the issue.

Philosophy-driven approach unsuccessful in North Oakville

The strategy outlined by Steer follows themes that have become familiar over the last two decades: build denser housing to create more walkable communities, add pedestrian connections and bike lanes, invest in transit options.

It’s a philosophy-driven approach that hasn’t succeeded in North Oakville, where planning for a less car-dependent society has resulted in a dense community with serious parking problems.

Ward 7 councillor Pavan Parmar, who represents the area north of Dundas Street, suggested staff should consult with the North Oakville community “to understand what didn’t work.”

Similar parking woes exist in the dense and walkable Oak Park area, where Ward 5 councillor Jeff Knoll says residents still jump in their cars to make a two-minute trip to the convenience store.

Other attempts to change the automobile-focused habits of Oakville residents have also been largely unsuccessful.

In 2013, the town approved a transportation master plan that set the goal of getting people out of their cars for at least 32 per cent of trips by 2031. The vision was that transit would provide 20 per cent of trips, while walking, cycling, car pooling and other methods would add up to another 12 per cent.

Lack of progress toward that goal resulted in a 2017 review of the transportation master plan downgrading the goal to 24 per cent of trips by 2031.

Promoting options

While managing growth to develop denser communities with walkable features is a key element of the strategy, it also offers a range of other ways to encourage people to get out of their cars.

Those include making cycling, transit and pedestrian options “just as easy as hopping in your car,” said Abda.

A series of “quick wins” suggested in the strategy include lengthening traffic signals and lowering speed limits to make pedestrians more comfortable, along with adding rumble strips to separate bike lanes from vehicles and providing secure bike parking at key nodes.

In the longer term, it calls for investments in expanded bike lanes, a bike-share program, winter maintenance of bike lanes, better signage for cycling and advancing key transit priorities.

Ward 1 councillor Sean O’Meara asked whether the planned approach makes it easier and quicker to take transit or harder to use cars.

While Abda said, the plan is to make it easier to get around in ways that don’t involve private cars, the town’s growth will ultimately bring congestion that slows personal vehicles.

“Quite frankly, we don’t have to do anything to make it harder to drive,” he said.