Dan Levy from the hit Canadian show Schitt’s Creek has been telling us all we need to learn more about the First Nations, and recommending we take the University of Alberta Indigenous History online course. So, I did. I followed it up with some reading, which if you are interested you will find at the end of the article.

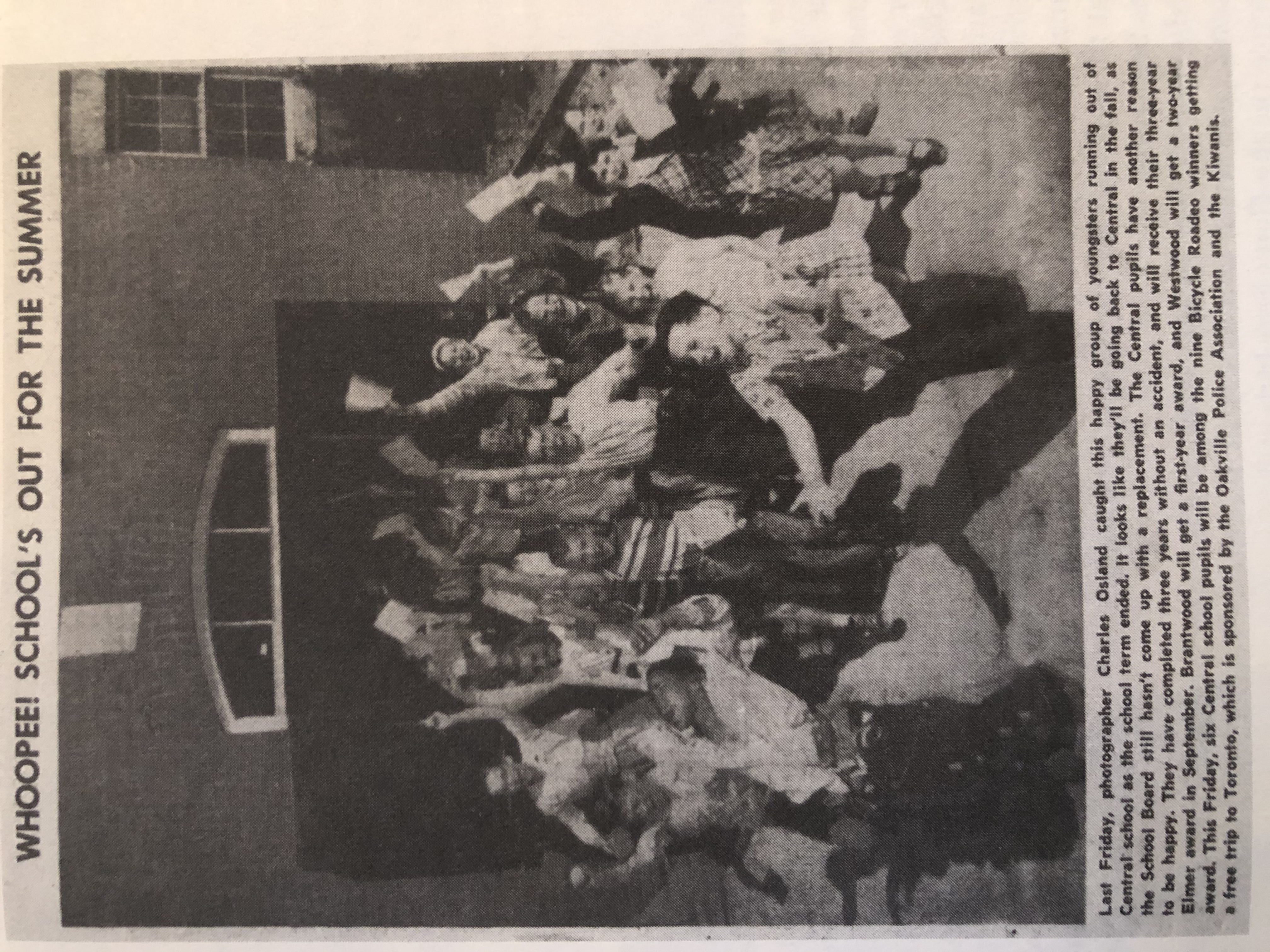

Two of the authors had Oakville connections. John Ralston Saul went to Oakville Trafalgar High School, and Professor Don Smith grew up in Oakville and attended Central School and Oakville Trafalgar. Professor Smith's Seen but Not Seen was particularly informative. He describes indigenous history and culture as being all but ignored in that era, which is enlightening considering that Hazel Matthews describes children finding arrowheads on the Central School site regularly in the 1800s, in her book Oakville and the Sixteen.

Also tremendously helpful as I came to terms with this subject was Halton District Shool Board guide to indigenous knowledge, Stephen Paquette.

The course and all my reading were pretty well in agreement, and this is what I took away from it. This is one man’s attempt to make sense for himself of a past he has inherited, and should not be seen as more than that.

Europeans arrived on our shores with a mindset of cultural superiority, exemplified by the Doctrine of Discovery, which gave papal blessing to Christian countries colonizing new lands. They were told by the Pope that if they found any new lands inhabited by non-Christians, they could and should convert them to Christianity, and if they refused, enslave them and if they resisted kill them. This illustrates the ideological underpinnings that supported a mindset of privilege and entitlement, conveniently aligned to the acquisitive drive of the colonizing Europeans.

Yet, beginning with Jacques Cartier, Europeans needed help from the people they found already living in what became Canada. Cartier’s settlers got scurvy over the winter and only survived because First Nations people showed them which tree bark to boil to ward off the disease.

History books may call them “explorers”, but in reality, Europeans had a guided tour, employing natives to help them “discover” the country the First Nations people knew very well.

As the fur trade developed, the new arrivals depended on the First Nations for supply and traded with them. In a context where rural serfdom still existed, replaced only by the oppression of working people in the industrial revolution, this represented European commercial dynamics displacing the highly developed trading relationships that existed among First Nations before the European arrival. First Nations fell victim to the same exploitative relationships that controlled the mass of ordinary people in Europe.

Along with this commercial contagion came European diseases to which First Nations had no immunity, sometimes carried in the trade goods swapped for furs. This resulted in devastating population loss. In spite of all this, the arrangements continued for more than a century and in relative terms improved the prosperity on both sides. No commercial arrangement lasts that length of time unless some mutually beneficial accommodation has been reached. Indeed, there are many examples of intermarriage, and children of these marriages could be accepted. As an example, one was the factor at the Hudson’s Bay post in Edmonton. The fur trade further illustrates the dependency of the Europeans on First Nations in establishing themselves on the North American continent.

In the wars with the Americans, First Nations were essential to our success and fought courageously and very effectively. It is highly probable that without the help of the First Nations people in the War of 1812, Canada would not exist today.

From the perspective of the First Nations peoples, we would co-exist as equal nations with different cultures, collaborating for mutual benefit. Yet the British reneged on many of the undertakings that were made with Tecumseh to ensure his and his allies’ help in the War of 1812. It was Sir Isaac Brock who had made these promises, and his death at Queenston was the end of the British side of the bargain. Tecumseh held up his side and was critical in turning back the American attack and making it the last actual military aggression in the doctrine of “Manifest Destiny” to control the North American continent which held sway in the United States.

On a technological level, Indians did not have gunpowder (which Europeans had acquired from the Chinese), but among other technologies adapted to the land they inhabited they had canoes, which proved decisive for the British on the Nile in Egypt, under the general for whom Kitchener, Ontario is named. (Ironically, the British had confirmed the military value of canoes by using them to move troops to crush the North West Métis rebellion in Manitoba.)

However, once the War of 1812 was behind us and the fur trade had dwindled, British North America began to work on nation-building…instead of valued partners, without whom settlers could never have achieved success in economically exploiting and colonizing this new land, First Nations peoples were now outnumbered and an inconvenience. In short, Europeans didn’t need them anymore, and they were in the way.

Much trust had been built up and using that the government negotiated treaties which First Nations first of all believed we would honour, and often in any case understood as land-sharing arrangements. We did not always honour them and, ever-pragmatic, our interpretation was of land title surrender.

“When treaties were signed between Indian (sic) First Nations and representatives of the Crown, the Indian (sic) First Nations viewed themselves as independent sovereign nations entering into formal treaty agreements and relationships with another sovereign nation.” (Harold Cardinal, quoted by Donald B. Smith, Seen But Not Seen.)

Yet negotiations took place in the language of the British, contributing to an unfair and unequal understanding of the terms, and the legal structure of the colonizers held sway. The traditional treaty documenting instruments of the First Nations people, the wampum belt, were brushed aside as uncivilized.

Our need to settle the land to secure our control of it given the ever-present threat from the south led to more and more such arrangements—to the point that First Nations peoples found themselves unable to maintain their traditional economic practices over ever-diminishing territory. Wanting even more land to be ceded to the Crown, and by now significantly outnumbering the First Nations population, we ceased all pretext of dealing as equals, nation-to-nation. Through this process, First Nations peoples and Inuit became wards of the state, under the infamous Indian Act.

The legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery was alive and well. We embarked on a process of assimilation, in the belief that indigenous culture was backward, not simply different but indeed inferior, and that indigenous people would best be served by abandoning their culture and embracing European ways. If they did this, they could become full citizens, with the right to vote, but if they did so they would surrender their First Nations’ rights, which conveniently would free up more land for settlement and resource extraction.

This led to the residential school system, which was designed to remove children from their own culture and prepare them for integration into the settler culture.

While there were doubtless well-intentioned people believing they were improving opportunities for indigenous people involved in this, it aligned well with the assimilation approach to eliminating the First Nations people as an obstacle to colonization. First Nations people understood that they could learn from Europeans, as Europeans had learned from them, and they supported schooling, but asked unsuccessfully for schools to be on the reserves. The government was convinced assimilation required First Nations stop being First Nations. To achieve that objective, children had to be removed from their parents.

We have all seen and heard much over the past few years about the abuses within the residential school system, and the cultural genocide they represented. Wanting to integrate the children into white culture, but at a time when schools for Europeans were largely parent-funded, and governments did not pay for free education, the government tried to do it as inexpensively as possible. To do so it enlisted the churches, who saw the schools as an opportunity to spread the word of God and expand their influence. Even though for the rest of the population, education was publicly funded starting in 1871, this did not change. Indeed, to this day there is less funding per child for indigenous children than for the rest of the Canadian population.

The power and discipline relationships common to European schools at the time were entirely foreign to First Nations peoples, who corrected children with example, patience and kindness. School facilities were unhealthy, nutrition was poor, and apart from the emotional toll, many children (as many as 60% in some cases) died before or soon after returning from the schools. Sexual, physical and emotional abuse were widespread. Generations of children grew up outside their own culture of family, such that the cycle of modelling how to parent was broken. This lost knowledge is all but irreplaceable, and is behind many of the mental health, alcohol and substance abuse, suicide, depression and spousal abuse issues that are more common among indigenous people than in the settler population. These are the reasons that indigenous people have rightly been successful in pressing claims for compensation for the harms done by residential schools.

In another perhaps well-intentioned effort to deal with the consequences of these awful institutions, the children of parents so damaged by them as to be unable on their own to raise them were removed from them, in what is called the Sixties Scoop, and adopted out to settler families. Oakville resident Stephen Paquette

was a victim of this event, and grew up in a settler family. He tells the story that when he was ready to apply to University and had ambitions of attending law school, for which his academic record showed the potential, his otherwise loving and supportive adoptive parents put the kibosh on his idea. As a First Nations child, he would not have the ability, they had been told at the time of the adoption, and they could not shake that belief. Steve is now the Halton District School Board guide to indigenous learning.

This carried on until the last residential school closed in 1996. First Nations people could not vote without giving up their “Indian” status until 1960. This can be traced to the Indian Act of 1876, which defined what it meant to be an “Indian”. This included loss of status for women marrying outside the First Nations community, but not for men. Many First Nations tribes were matriarchal in structure, so once again this was an imposition of culture inconsistent with any illusion of equally sovereign nations. The Indian Act subsumed a number of colonial laws that aimed to eliminate First Nations culture in favour of assimilation into Euro-Canadian society. It is an evolving, paradoxical document that has enabled trauma, human rights violations and social and cultural disruption for generations of Indigenous peoples.

Canada’s success in moving from a country where Catholics and Protestants, even when mostly Christians of British origin, were wary of each other well after World War II, to our current multicultural state, is a remarkable achievement. By contrast, settler interactions with the many different indigenous peoples with whom we at first collaborated, if inequitably, to enable our mutual success on this continent, are an awful stain on our history. One that has, as we are often reminded in the media, left real scars, indeed open wounds.

One optimistic takeaway from the course and reading is that at least among government officials, there was surprisingly little indication of biological racism: the idea that not only the European culture but the European race is superior to the indigenous people. The general belief seems to have been that given the tools, indigenous peoples could adapt and compete in European society. Sir John A. Macdonald’s policies towards indigenous peoples were sometimes ruthless (“I have reason to believe that the agents as a whole … are doing all they can, by refusing food until the Indians are on the verge of starvation, to reduce the expense,” Macdonald told the House of Commons in 1882, to the approval of both parties).* Yet he had indigenous friends. One of them, Oronhyatekha, who became a medical doctor, chose not to assimilate (“enfranchise”, or take the right to vote in exchange for abandoning his treaty rights). Macdonald said he could understand the man wishing to retain his tribal links, just as his own forebears had cherished clan links in Scotland. (Scots were of course another group cleared from their lands by the English.) Oronhyatekha felt that MacDonald respected indigenous people having taken the idea of confederation from them, and named his son John Alexander after the Prime Minister.

*It should be said that at this point in history governments did not provide food or welfare for their citizens. Only because First Nations economies had been broken by the loss of land did the government feel any obligation to send food. But withholding it was leverage in bringing First Nations to submit to European rule.

Many other influential Canadians had close personal relationships with indigenous or mixed individuals. Even Duncan Campbell Scott, the chief architect of the residential schools, had friends who had intermarried, and interacted with their spouses and children as equals. In other levels of society there no doubt was, and we know there is now, the ugliest kind of racism towards indigenous peoples, but in spite of the colonizing impulse and belief that European culture was more advanced, there seems to have been confidence at the official level that indigenous people were as capable and intelligent as settlers and needed only education to assimilate. The memory of how important they had been to the very existence of the new Canadian nation had perhaps not entirely faded.

In any case by all reports in my reading, it is hard to find examples of biological racism at the official level. Instead, there was a belief in a social evolutionary hierarchy where European society is perceived to have advanced to a higher level than the indigenous society. Indeed, official statements express a belief that if left to themselves indigenous people doubtless would have developed a more advanced society on their own, implying that the arrival of Europeans means they will need to make that advance more rapidly. Today’s social scientists would reject the hierarchical evolutionary society view, considering that diverse cultures have different but equally valid modes of organization, and comparing them is like comparing apples and oranges.

Broadly speaking, our government until recently has pursued a policy of wanting the First Nations not to go away, but to stop being First Nations and assimilate. This approach was still alive and well at the time of the 1969 White Paper under the government of Pierre Trudeau.

It absolutely hasn’t worked. In spite of government’s best efforts to eradicate indigenous cultures, they have survived, and after dramatic population reductions owing to the destruction of their economic systems and to European disease, aboriginal peoples now represent the fastest growing population group in Canada. That is fortunate for all of us, as we still have much to learn from them, just as every cultural group brings best practices that enrich our country. But while we can reasonably expect that those who choose to come to Canada understand and adopt the customs of their chosen country before making their own unique contributions, we might heed our own words before expecting those who welcomed us here to abandon their own culture to that of the newcomers.

The European attempt to assimilate indigenous peoples into our culture and to erase theirs has paradoxically provided them with some tools that help them preserve it. They now have a common second language, either English or French, with which to communicate with each other, and more and more of them are learning the legal mechanisms and traditions which have been used against them, or even have been ignored in the process of colonization: legal mechanisms of one sovereign nation imposed on another. With collective action and an understanding of our culture, they are beginning to defend and restore their own. This has meant legal action, including many cases which indigenous groups have successfully taken to the Supreme Court, as well as protective actions and blockades. In some cases, these were necessitated by government failure to recognize indigenous rights, and have resulted in important changes.

It is not going to be easy to move to self-government and reinvigorated indigenous culture, while ensuring that all Canadians have unrestricted opportunities to reach their potential. Our country has become comfortable with a variety of different ways to accommodate having common interests and yet respecting differences. Respecting Québecois culture is achieved differently from respecting the cultures of new Canadians from South Asia for example, and both are a work in progress. Every culture has something to gain from learning about every other culture. We have much work to do in learning a new accommodation between our indigenous peoples and the settler population. Mutual respect and rebuilding trust will be the keys to a productive coexistence, but the gulf is wide. (If you are interested in the legal mechanisms needed to navigate this work, here is an excellent analysis of them.)

My reading for this primer.

The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America, Thomas King, Anchor Canada 2012

A wryly told story by an American Indian now living in Canada. Very readable and consistent with the academic version: a history in an accessible narrative form. Entertaining.

21 Things you may not know about the Indian Act, Bob Joseph, Indigenous Relations Press 2018

Some hard evidence of how the government legislated the status of native Canadians as wards of the state, determined that women lost that status if they married non-indigenous people, but that men and their children kept it, and many other examples of a paternalistic approach to getting rid of the Indian problem by absorbing Indians into settler culture. The author is a Canadian Status Indian, the son of a hereditary chief, and a member of the Gwawaenuk nation.

A Fair Country, John Ralston Saul, Penguin 2008

Like Professor Don Smith below, John Ralston Saul spent some years at Oakville Trafalgar High School. He went on to become one of Canada's leading intellectuals. This book is interesting view on the founding of Canada as a “Métis nation”, with many insights into behaviours which Canadians identify as ours without recognizing the contribution indigenous peoples made to them: the vaunted genius for compromise for example.

The Comeback - How Aboriginals Are Reclaiming Power And Influence, John Ralston Saul, Viking, 2015

In this book Saul describes the reinvigoration of indigenous Canadians in culture, economy, numbers, and self-determination. You can’t read this without realizing that this issue is going to matter more and more, and how we deal with it will have an enormous effect on social cohesion and stability, and thus prosperity and happiness, for all Canadians.

The Order of Good Cheer, Bill Gaston, 2008

Historical fiction, this really wonderful book takes some licence but tells the story of the interaction of Samuel de Champlain, the father of New France, with the indigenous people he worked with to make the French settlement succeed. The need for cooperation runs through the narrative, the organizing feature of which is a joint feast between Champlain’s colonists and the Indians. A richly written novel with sub plots and colour, with authentic insight into Champlain, who believed the French and the First Nations were two noble races whose joining together could only bring good.

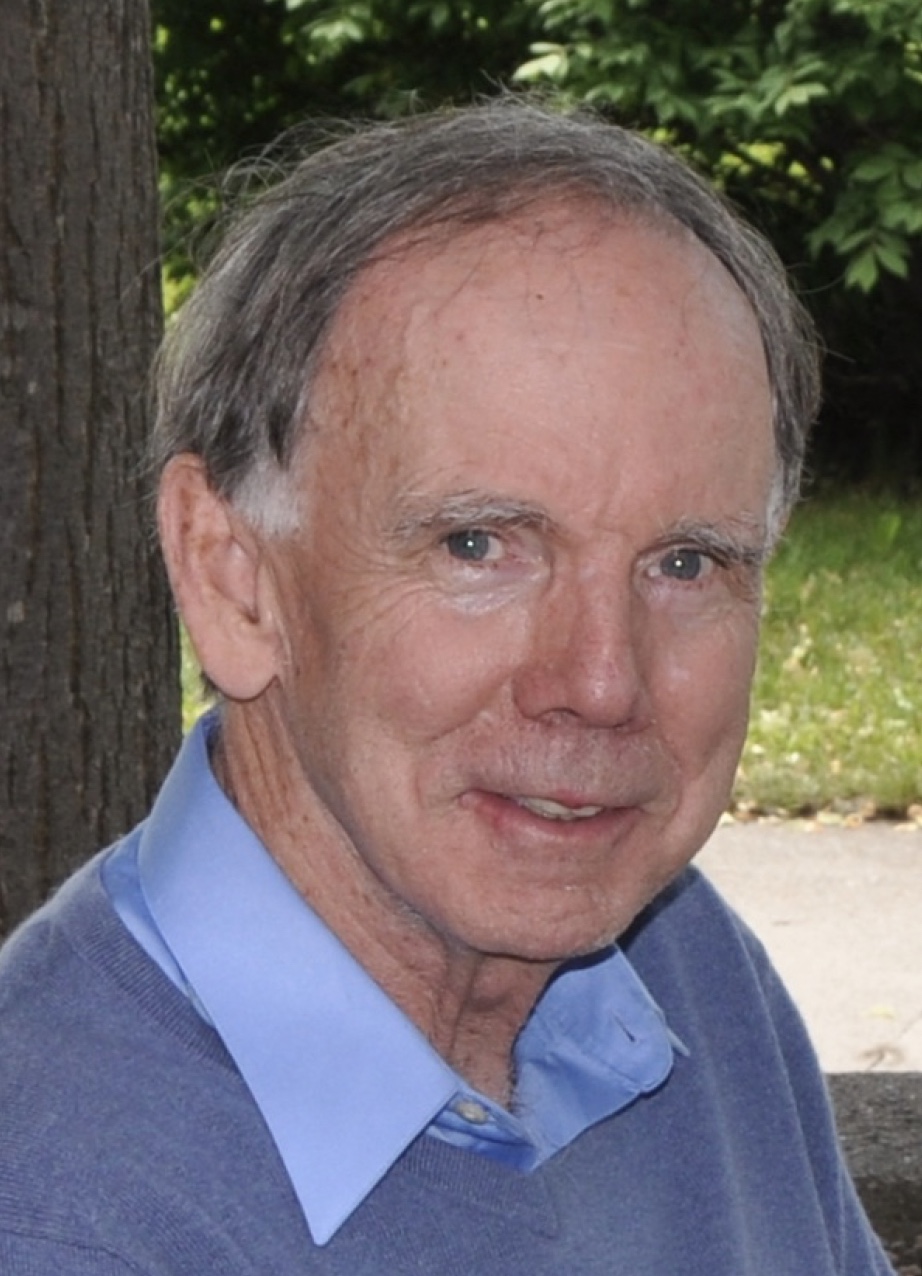

Seen but Not Seen: Influential Canadians and the First Nations from the 1840s to Today, Donald B. Smith, University of Toronto Press, 2020

I have saved this one for last not only because it is the most recent, but because the author, Donald B. Smith, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Calgary, grew up in Oakville, attending the Central School which stood where the Oakville Centre for the Performing Arts now is. The book is excellent, balanced and illuminating. While it is factually very rich, as well as researched and referenced, it is very readable and accessible. I found it of particular interest because it aligns with the facts that are presented in indigenous versions of the history, and also with their conclusions, although it is written by a non-indigenous historian, and addresses the interactions of prominent non-indigenous Canadians with First Nations peoples beginning with the period after the war of 1812, when settlers began to seriously outnumber indigenous Canadians and official Canada had begun to see them no longer as allies, but as obstacles to nation-building.

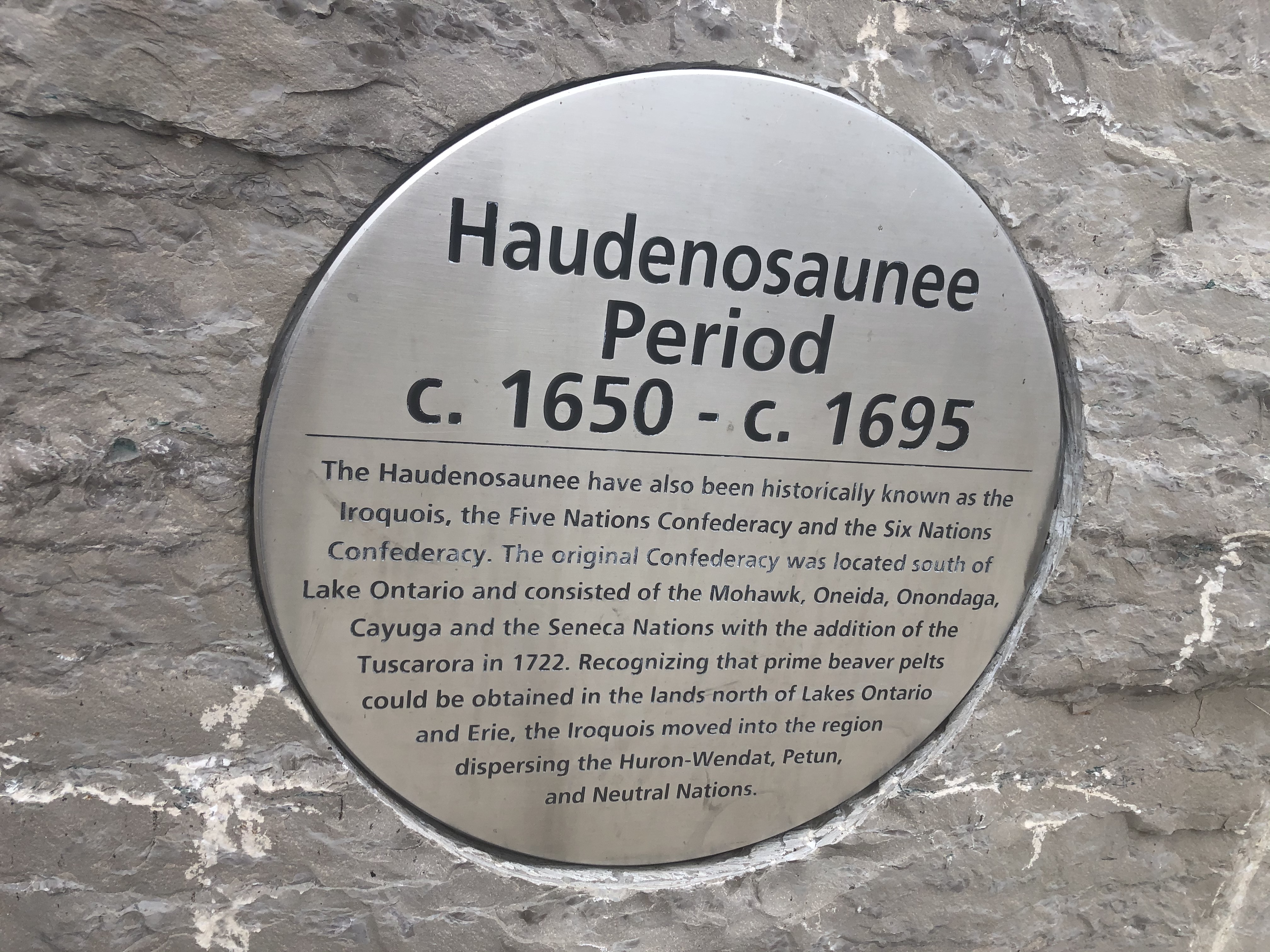

Illustrative of the path we are on, Professor Smith points out that as a child growing up in Oakville, there was little if any reference to First Nations peoples. The book talks about the tribes that inhabited our area, and the treaties that made it possible for us to occupy this land. As his brother Ian, who still lives in Oakville, points out, the combination of Streetsville, Port Credit and Clarkson that bears the Indian name Mississauga did not come into being until after Donald had left Oakville for university. Contrast that to today, when the Town’s new Tannery Park offers a prominent series of plaques detailing the history of the First Nations tribes that called the north shore of Lake Ontario home, we acknowledge who owned the land before us at public meetings, and Dan Levy convinces thousands of Canadians to take an online course in indigenous history.