February is Black History month – a month to celebrate African diasporas' stories, achievements, and contributions in Oakville and beyond. As our society takes stock in the second year of the pandemic, the stories of Black Canadians seem especially pertinent.

"It’s about a people who went through great adversity and rose above," says Lezlie Harper, tour operator and descendent of freedom seekers who settled in Fort Erie in 1851 in what was then the British colony of Upper Canada.

"We come from faith in God and our prayers and never giving up. We celebrate Black History Month because we rose above our circumstances in Canada and the US. Black history is for everyone."

Thanks to the conservation efforts of Black settlers' descendants and other guardians of local history, present-day Ontarians have a wealth of local and regional historical sites where we can learn about Black history.

As a relatively recent arrival to Ontario, I was interested to learn more about the Black history of the area. Earlier this month, I invited Oakville-based Nigerian-Canadian children’s book author Ekiuwa Aire to join me for a visit to some of the sites mentioned in the TVO article, "Ontarians should know more about the Black history of Oakville."

Here are some notes from our tour.

Our first stop was the James Wesley Hill House 457 Maple Grove Drive, now a private residence in the stately southeast edge of Oakville. There is a historic buildings plaque on the house, but no convenient street parking on the narrow road in front of the house.

Nevertheless, it was still possible to drive by and imagine how the farmhouse once stood in the mid-1800s, surrounded by strawberry fields and inhabited by the Black pioneer and freedom seeker James Wesley Hill.

According to the Oakville Images website, Hill came to these parts from Maryland in the 1840s. He sent his first earnings back to his enslaver as payment for his freedom. Some reports indicate he came across the border in a packing crate aboard a schooner.

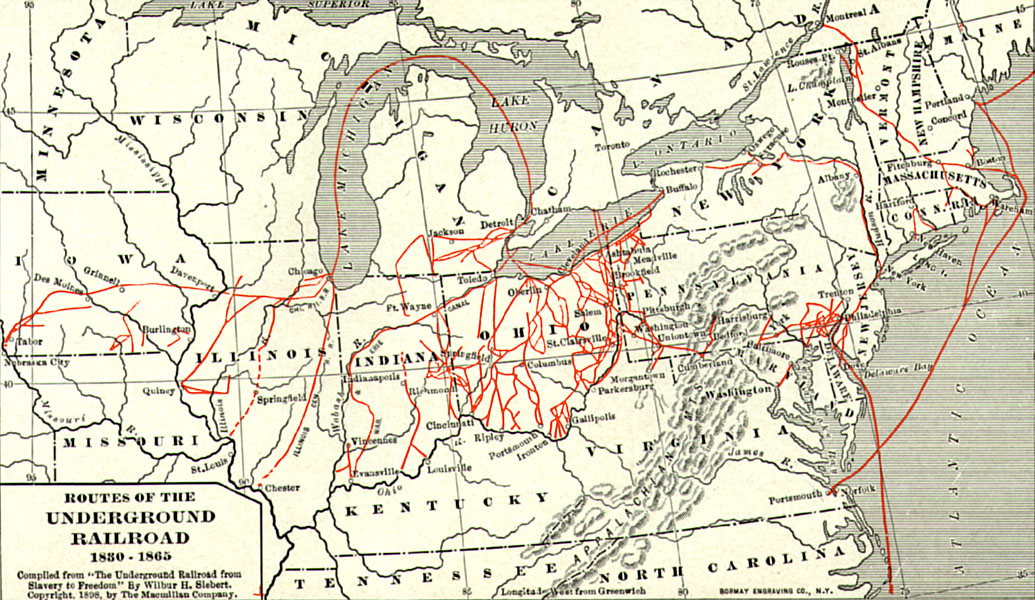

Oakville was then part of the Province of Upper Canada, and the land around the mouth of Sixteen Mile Creek served as an international port of entry. Through this port, Black refugees would have been smuggled out of the US after 1834, when a British Imperial Act came into force, ending the enslavement of Africans in the British Empire, including Canada.

"Once you crossed the water into Canada, that was the end of the Underground Railroad," Harper says. "If you want to go on further, you could. But they couldn’t extradite you back after 1834. You were free."

Having achieved a degree of prosperity in Oakville, Hill built his home and established a strawberry farm that helped make Oakville the one-time strawberry capital of Canada. He returned to the United States numerous times as a "conductor" for the Underground Railroad helping other Black American refugees find safe passage out of the US into British North America.

Refugees arrived in the largest numbers after 1850 when the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act granting enslavers the right to recapture any escaped slaves, even if they were living in one of the free states.

We next drove to Oakville’s downtown harbour to visit 41 Navy Street. It was once the retirement home of the British captain Robert Wilson for five years from 1883 to 1888, when he died at the age of 82. Wilson ferried hundreds of refugees across Lake Ontario to safe haven in Oakville and beyond on his fleet of small watercraft during his career.

To learn about Black history, the Wilson residence is conveniently located across the street from the Oakville Museum at the Erchless Estate, home of the permanent Black history exhibit: The Underground Railroad: Next Stop, Freedom.

When we visited, the museum was closed, but with a bit of planning, one could take in the exhibit and tour. Entry is by donation, and there is no need to reserve in advance. Tours operate on a first-come, first-served basis.

The Black history exhibit is located on the second floor of this historic building and is not yet wheelchair accessible. Oakville Museum is usually open Tuesday to Sunday from 1 p.m. to 4:30 p.m., but it will be open this Family Day Monday from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m.

Museum staff shared that Captain Robert Wilson had built an earlier house in 1862. Known as the Mariners’ Home at 279 Lawson St., it faces George’s Square. Black refugees he helped would gather in the square on Emancipation Day (August 1) for a picnic to commemorate his role in their journey.

Our last stop was Turner Chapel at 37 Lakeshore Road West. It is now the site of an antique shop but was once a thriving African Methodist Episcopal Church and the heart of Oakville’s Black community. According to this 2003 Oakville Beaver article, the organ was once played by the grandfather of the actress Arlene Duncan. Her great grandfather was at one time the minister.

Inside, we were greeted by Robert Gardner, a retired academic and history buff who was eager to share what he knew about the building and its history. Gardner says the Black settlers fleeing the Fugitive Slave Law might not have conformed to popular notions of who former slaves were.

"People might be quite happy to think that they were coming here as poor benighted souls, but they weren't," Gardner explains. "There were artisans and skilled people who were capable of making a living. There were carpenters, blacksmiths and glaziers. When they arrived, everything had to be done, and they knew how to do it because when they came here, they had a lot of skills."

One skill, in particular, was the knowledge of how to operate stone boats to haul slabs of sedimentary rock out of Lake Ontario. The harvested stone was a source of wealth as a valuable commodity used in constructing buildings in the area, many of which are still standing.

Looking at the exterior of the Turner Chapel, Gardner points out the fine brickwork and arches, the work of master bricklayers. Hours for the Turner Chapel Antiques and Appraiser are Tuesday to Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sunday from noon to 5 p.m. The store is closed Monday and will be closed on Family Day Monday.

After our short tour of Oakville Black history locations, we reflected on what we had learned.

"History is closer than what we think sometimes," Aire says. "When you think of Black History Month, you often think of the United States, Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks."

"We maybe don’t realize that here in Oakville, there’s a whole building you can drive down to see bricks that were laid by the descendants of people who were moved involuntarily from their homes in Africa. Black History Month is a good opportunity to connect those dots and spark that conversation."

According to the Levy article, in the decade after the Fugitive Slave Law, it’s estimated that Black people represented some 20 percent of the town’s population of 2,000 people. If they could find prosperity here and build such a fine church, where did their progeny go, and why did they leave?

I asked Harper that question when we spoke on the phone. Harper says many freedom seekers who arrived in the immediate aftermath of the Fugitive Slave Law returned to the United States when conditions became more favourable. But others, like her family, and Duncan family, did stay on in Canada, contributing to the fabric of Canadian society ever since.

If you and your family are looking for something fun and educational to do, consider taking Harper’s Black history tour, which she runs out of St. Catharines.

At the time of publication, there were still spots available for her Family Day weekend Niagara Bound Tours. In normal years, she leads motorcoach tours. Still, in light of the pandemic, she has shifted the tour to be a wholly outdoor and contactless car-caravan to historic sites significant to Black history in the Niagara region. The tour takes about three hours and costs $150 per car (for a maximum of five participants).

"Happy Black History Month," Harper says. "Please celebrate how these people rose above. Yes, there’s racism out there, but we have the shoulders of all these amazing people to stand on."