Ontario’s 1943 provincial election saw a number of firsts. It was the first of 13 consecutive elections where the Progressive Conservatives won the most seats. It was the first time the CCF, the predecessor of the NDP, formed the official opposition.

And, in two downtown Toronto ridings, it was the first time Communists were elected to the Ontario Legislature.

A small contingent of Communists maintained a presence at Queen’s Park well into the post-WWII red scare era.

Banned off and on since forming in Guelph in 1921, the Communist Party of Canada developed strong ties with elements of Toronto’s labour movement, such as unions involved in the garment trade.

By the 1930s, Torontonians had elected two Communists to city council, representing wards that included the industrial areas of the Garment District, Kensington Market and Trinity-Bellwoods.

Those neighbourhoods also supported the party, which reorganized as the Labour-Progressive Party (LPP) after the Communist Party was officially banned under the War Measures Act, in the 1943 provincial election.

The LPP benefitted from its support of Canada’s role in the Second World War and from the Soviet Union joining the Allied effort.

Toronto’s favourite Communists

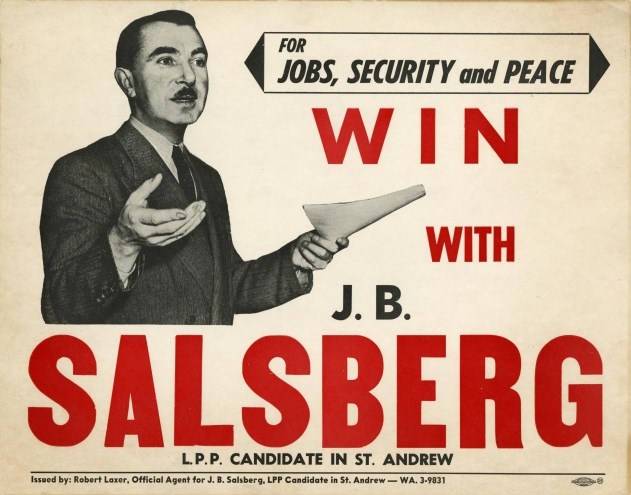

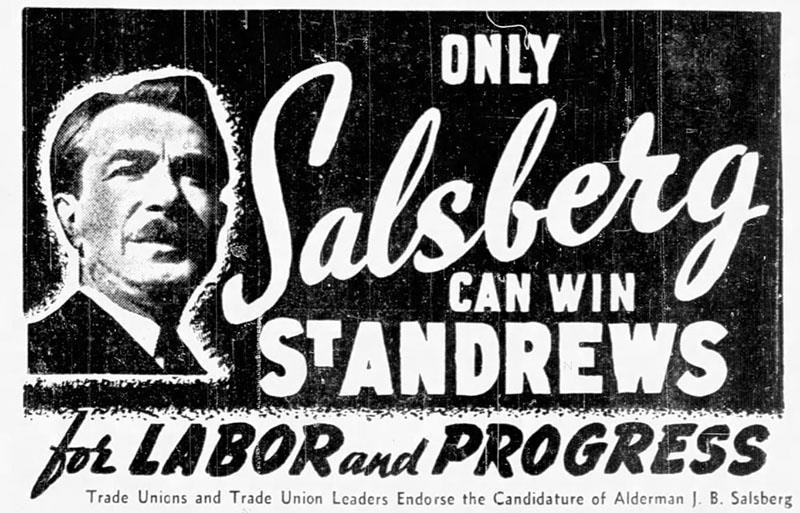

Among the Communists elected was J.B. Salsberg, a labour activist in the garment trade and sitting city councillor with strong ties to the Jewish community centred around Kensington Market.

A strong campaigner, Salsberg was known for spending hours walking around the neighbourhood to talk with constituents.

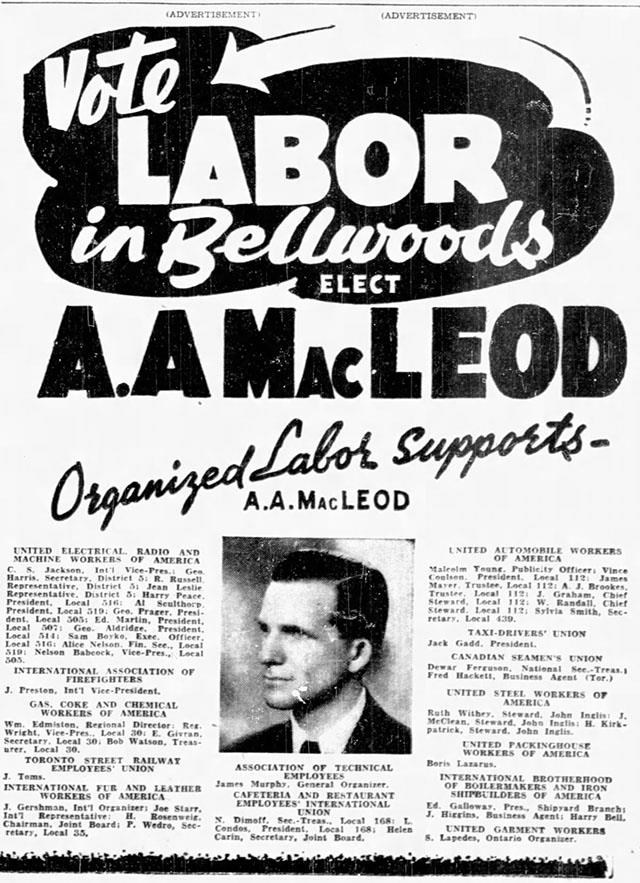

He won the riding of St. Andrew by a landslide, receiving more votes than his three challengers combined. In Bellwoods, voters elected A.A. MacLeod, an anti-Fascist activist who had edited the party newspaper.

With a caucus the same size as the Green Party of Ontario has today, MacLeod and Salsberg zeroed in on labour and social justice issues, earning themselves a reputation as the social conscience of the legislature.

According to Salsberg’s biographer Gerald Tulchinsky, the two MPPs “performed like a well-matched wrestling tag team, the one picking up where the other left off, relentlessly questioning a minister or government member or responding either to an evasive or limited answer or to a crude anti-Communist barb.”

Sometimes they helped shape government policy.

During the winter of 1944, the two Communists proposed anti-discrimination legislation to then-premier George Drew, who required their support to keep his minority government in power.

In a letter to Drew, Salsberg cited nearly a dozen recent examples across the province of discriminatory acts against Blacks and Jews.

Salsberg drafted a bill that addressed discriminatory practices in employment, housing and real estate. However, few of those provisions remained when the Racial Discrimination Act passed in March 1944.

Red-baiting in the legislature

Drew often resorted to red-baiting after winning a majority in the 1945 election, souring relations with the Communist MPPs who he accused of having “vile anti-Christian doctrines.”

Both Salsberg and MacLeod had been re-elected that year. The LLP’s ranks also grew with the addition of three MPPs who had run jointly for the Liberals and LPP as “Liberal-Labour” candidates.

When Drew lost his High Park seat in 1948 — and MacLeod and Salsberg retained theirs — a parade of 5,000 LPP supporters marched between Queen and College streets, chanting “we’ll hang Drew on a sour apple tree.”

When police showed up, the crowd pivoted to singing “O Canada” and were guided through intersections by the cops.

If Drew wasn’t fond of MacLeod and Salsberg, his successor felt differently.

Progressive Conservative premier Leslie Frost deeply respected them, once suggesting that “those two honourable gentlemen” had “more brains than my entire backbench put together.”

Rumour had it that Frost had even offered Salsberg a cabinet position in exchange for crossing the floor to the Tories — although he never did.

When MacLeod was defeated in 1951 amid intensified anti-Communist hysteria, Frost observed that “without him in the legislature, some of the lights went out.”

Left alone as Queen’s Park’s solo Communist after 1951, Salsberg continued to carefully criticize the government during debates on labour and social policies.

While continuing to publicly support the Soviet Union, he developed doubts, especially as reports about purges — particularly those against Jews — were leaking out.

There were some miscues, however, including Salsberg's decision to praise Joseph Stalin in the legislature following the Soviet dictator’s death in 1953.

Goodbye to the Queen’s Park Communists

Over the years, Salsberg fended off several noteworthy Progressive Conservative electoral opponents, including lawyer Eddie Goodman and future Toronto mayor Nathan Phillips.

But by 1955, as his base grew more prosperous and began moving to the suburbs, some Jewish community leaders had begun to view him as an embarrassing throwback whose Communism did them no favours.

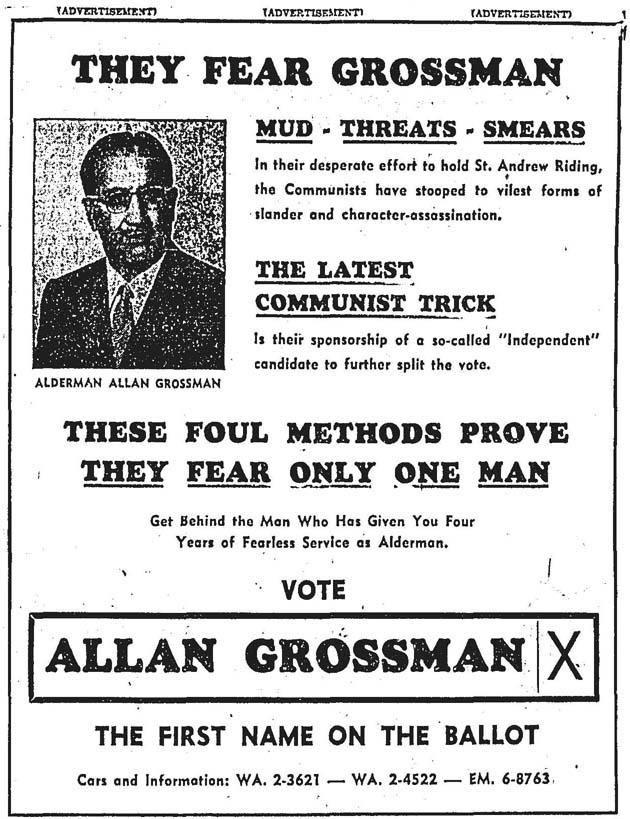

In that year’s election, Salsberg’s PC challenger was city councillor Allan Grossman, for whom the race was a battle between good and evil.

It was one of the dirtiest races in Toronto history.

Grossman’s family received threatening phone calls from LPP supporters. Salsberg complained that too many election officials were loyal Tories. A last-minute independent candidate turned out to be a former Salsberg campaign worker who was suspected of trying to engineer a vote split in the LPP’s favour.

On election day morning, Salsberg nearly wound up in a fistfight with a Tory riding official after his opponent’s campaign posters were spotted on vehicles transporting the special constables who oversaw the polls.

Soon after, two policemen noticed the fuel tank on Salsberg’s car was open and found sugar scattered around the fuel pipe.

That afternoon, several voters complained they received phone calls claiming Grossman had dropped out, while polling officials had to be issued police escorts after hearing threats that ballot boxes would be stolen at the end of the night.

Grossman won by just over 600 votes, ending the Communists’ presence at Queen’s Park for seven decades (and counting).

Salsberg finished third in a federal by-election that fall, marking the end of his political career.

The combination of a visit to the Soviet Union in 1956, where he witnessed plenty of antisemitism, and the official revelation of the horrors of the Stalin era led him to leave the LPP and ditch Communism the following year. He remained a social activist, worked as an insurance agent, and was a columnist for the Canadian Jewish News before his death in 1998.

MacLeod left the party around the same time and worked on human rights documents for the provincial government. His past — which included fighting as a teenager during the First World War — and his politics influenced his nephew Warren Beatty.

His life and humanitarian ideals were among the inspirations for Beatty’s 1981 Oscar-winning film Reds.

Frost remained in touch with both MacLeod and Salsberg following their departures from the legislature.

He believed, at least in MacLeod’s case, that he was never truly a Communist but was driven to combat injustice. In a letter written to a friend in 1968, Frost concluded that “they were men who were dissatisfied with the way of things.”

___

Jamie Bradburn is a Toronto-based freelance writer and historian, specializing in tales of the city and beyond. His work has been published by Spacing, the Toronto Star and TVO.